Their history dates back to the end of the 18th century. The bituminous coal deposits are hosted in the Upper Carboniferous clastic formations composed of sandstones, conglomerates, mudstones and claystones. Two underground geotourist routes located in old mine workings, Water and Family were developed in the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex. The Water Route connects the former bituminous coal mine “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) with the drainage Main Key Hereditary Adit. The tourists, partly, experience an unforgettable in time boat trip along the old drainage working, journeying above a kilometre distance there too. The Family Route is also located in old mine workings, where the coal haulage system is presented together with the historical underground railway, which carries the visitors along 1,5 km distance.

The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex also includes a number of surface post-mining objects concentrated around the old Wilhelmina and Carnall shafts available for tourists. Among them are a building of a 100-year-old steam hoisting machine, as well as other post-mining buildings, including the historic chain bath.

Up to now, great domestic and world popularity of the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit in Zabrze has made the city become a European centre of post-industrial heritage, associated with “black gold”.

Introduction

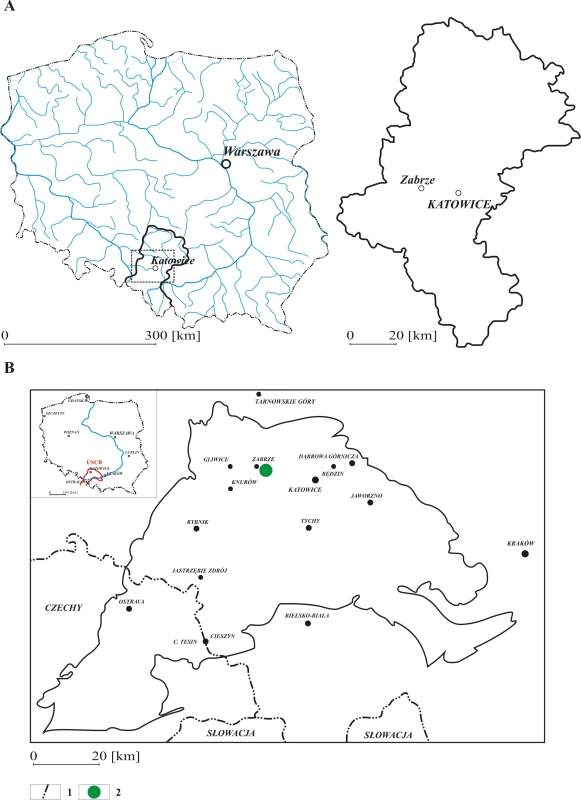

The historical “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit, developed for geotourism purposes is located in Zabrze city, in the central part of the Silesian Voivodship (Fig. 1A) and the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB) (Fig. 1B) (Jureczka et al., 2005; Stupnicka, 2007; www2). This is a complex created on the basis of original, historical buildings and excavations connected with each other: the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) bituminous coal mine (Dzięgiel, 2007) and the drainage Main Key Hereditary Adit (Bugaj & Glosz, 2012; Frużyński, 2012; Jurkiewicz, 2002; Jurkiewicz et al., 2009; Gola, 2020). Their history dates back to the end of the 18th century when most of Upper Silesia became part of the Prussian state. A widespread action was run then there with the aim to locate easily accessible coal deposits, a key source for the development of Prussian industry. The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) mine was the oldest one in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB) (Dzięgiel, 2007). Its operation was halted in 1998 due to reserves exhaustion and environmental issues. The Main Key Hereditary Adit, draining the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) coal mine in Zabrze city and the “Król” (“King”) coal mine in today’s Chorzów city was started to be drilled in end of the 18th century too. It was the longest hydrotechnical construction of the 19th century mining industry in European Coal Mining. Its operation was stopped in 1953 as it began to lose its importance (Bugaj & Glosz, 2012; Frużyński, 2012; Jurkiewicz, 2002; Jurkiewicz et al., 2009; Gola, 2020).

Some parts of the former “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine and the Main Key Hereditary Adit have already been opened for the public as underground tourist trails and geosites (Słomka & Kicińska-Świderska, 2004). The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine relic and its some surface post-mine buildings with mining equipment exhibitions were transformed into a complex museum and available since 1993. In 2000, the city authorities decided to connect this object with some relic of the drainage Main Key Hereditary Adit to make this facility more interesting and popular. In consequence, it has been called commonly the “Królowa Luiza (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex since 2018 (Gola, 2020; www3). This object is also a branch of the Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze, founded in 1981 (Frużyński, 2012). What is more, it has become so interesting and important around the world that it was included into the Silesian Industrial Monuments Route and European Route of Industrial Heritage too (Różycki, 2005; Nitkiewicz-Jankowska, 2006; Burzyński, 2007; Januszewski, 2009; Drobniak et al., 2020; www1; www5). It is part of a longer story about the transformation of European industry, the building of the economic power of Upper Silesia and the importance of mining heritage.

Methodology

Simple, standard methodology includes direct field observations and photographic documentation made personally at the described sites.

Geological structure of the central part of the Silesian District

Zabrze is located in the western part of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB) (Fig. 1B) (Jureczka et al., 2005).

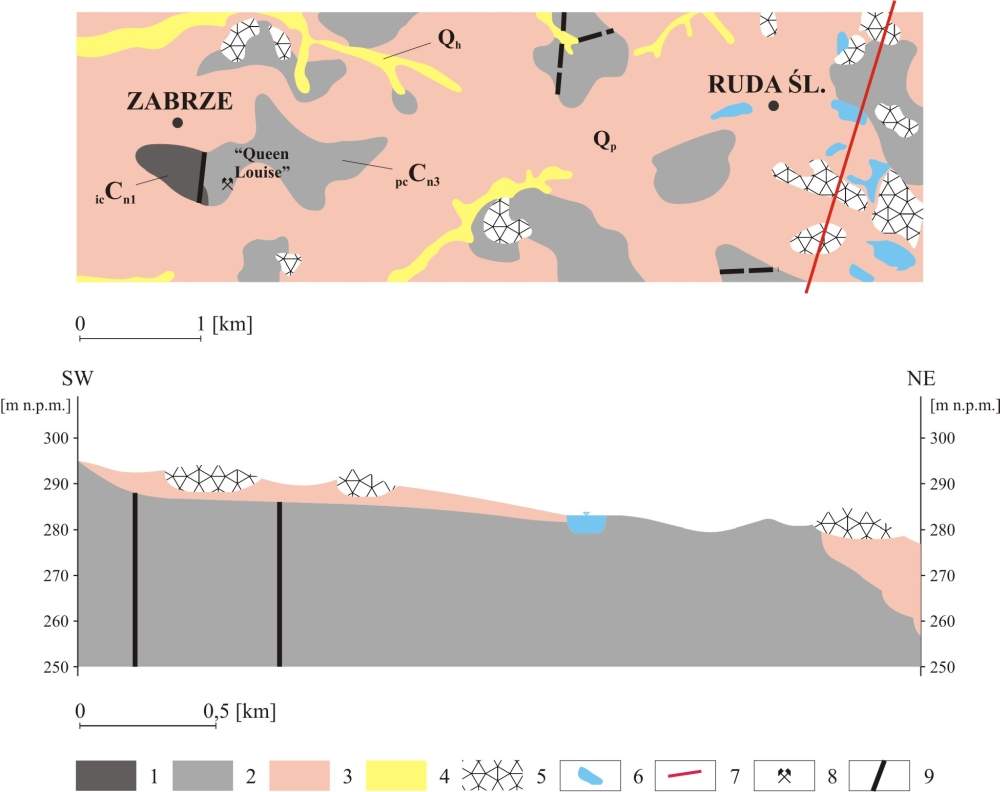

The central part of the Silesian District area is built of Upper Carboniferous and Quaternary formations. Upper Carboniferous rocks, hosting bituminous coal deposits occur all over the area. They are most representative in the vicinity of Zabrze where they crop out at several sites or are covered with only a thin overburden of Quaternary sediments (Fig. 2). Hence, the early coal mining operations have started just there.

The Carboniferous (Silesian) formation outcropped around Zabrze comprises two Upper Carboniferous series: paralytic (Namurian A) and Upper Silesian Sandstone (Namurian B and C). In that area, the paralytic series includes the Poręba Beds composed of claystones, mudstones and sandstones with numerous coal seams. The Upper Silesian Sandstone Series includes two members: the Anticlinal Beds (Namurian B) and the Rudy Beds (Namurian C), which host the largest coal reserves in the USCB. The Anticlinal Beds include gravelstones, sandstones, mudstones and claystones of thickness from 80 to 320 m, in which average cumulative thickness of coal seams is 28 m. The first one of them is called ”Pochhammer” and its number is 510 (Fig. 2) (Kotas & Malczyk, 1972a; 1972b; Ruehle, 1972; Kotas, 1995; Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015). The Rudy Beds, 530 m thick, include mudstones and claystones with cumulative thickness of coal seams varying between 15 and 20 m (Pawlak & Dziekońska, 1974; Gabzdyl, 1997; Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015).

Most of the vicinity of Zabrze area is covered with Quaternary glacial and alluvial sands of thickness about 10-20 m (Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015 ).

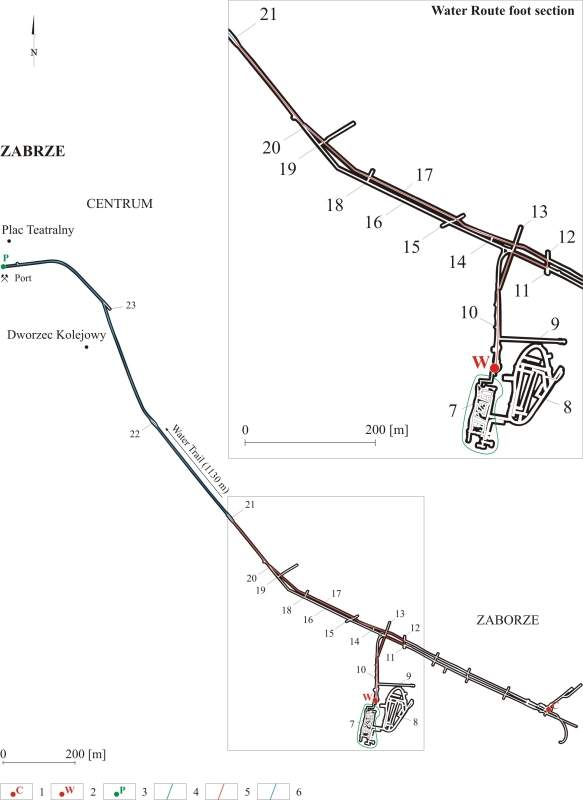

The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Luise”) Adit

The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit in Zabrze is a complex museum consisted of two main parts: the surface buildings, concentrated around the “Carnall” and “Wilhelmina” shafts (Fig. 3) and an underground exhibition based on more than 5 kilometres of historical mining corridors. These are some parts of the former “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Coal Mine’s and Main Key Hereditary Adit’s underground old workings open for tourists at present, organised as two underground geotourist routes: water (Fig. 3, 4) and family (Fig. 3, 5) since 2018 (Gola, 2020; www3).

The beginnings of coalmining in Zabrze date back to the late 18th century when most of Upper Silesia was part of the Prussian state. The region became an important element of the plan to expand the state power, based on a modern and independent economy, mainly on heavy industry. The Prussian authorities were mainly interested in mineral resources: iron ore, non-ferrous metals, and coal deposits. This task was carried out by Friedrich Wilhelm von Reden, a carefully educated visionary and reformer, since 1779 director of the Higher Mining Authority. Reden wanted to develop the iron and non-ferrous metal industry. The “Friedrich” steelworks in Strzybnica near Tarnowskie Góry, existing since 1784, was the first one in Upper Silesia. The next ones, in Gliwice and today’s Chorzów, were to be established. Hence, Reden decided the bituminous coal was the best resource for the metallurgical processes and commissioned a search for this mineral in Upper Silesia. In 1790, the existence of rich deposits in the vicinity of the villages of Zabrze and in Łagiewniki Górne (today’s Chorzów) was confirmed. In consequence, two state-owned mines were established in 1791: “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) in Zabrze (Dzięgiel, 2007) and “Książę Karol Heski” (“Prince Charles of Hesse”), quite quickly renamed “Król” (“King”), in today’s Chorzów (Gola, 2020).

Both the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Luise”) and “Król” (“King”) Mines faced one of the most serious threats in mining, the problem of incoming water. Therefore, a steam dewatering machine, imported from England and transported from the “Friedrich” ore mine in Tarnowskie Góry in 1795, was installed on the “Peter” shaft. However, it turned out to be unsuccessful in that mine. That is why, the drainage Main Hereditary Key Adit was started to be drilled in 1799. It was one of the biggest investments in the history of the mine. It not only solved the problem of drainage, but also improved the transport of coal (Jurkiewicz et al., 2009; Saja, 2009; Żurek et al., 2010; Bugaj & Glosz, 2012; Gola, 2020).

The Main Key Hereditary Adit intended to connect the two mines mentioned above. Running 14 kilometres underground, from the “Król” (“King”) mine, through the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) mine, it found its outlet in Zabrze, in the area of today’s Miarki street and near the Theatre Square (Fig. 3). It was extended by a water channel, connected with the Kłodnica Canal, which made it possible to transport coal to the Royal Iron Foundry in Gliwice. The adit was placed at a depth of from 40 metres in Zabrze till 70 metres in today’s Chorzów. The assumption was to drain the entire mining area between the state mines, including private ones. Another function supposed to perform was to transport coal from the excavations to the surface and make its seams accessible. It was calculated that floating the excavated material would turn out to be cheaper than pulling it out through shafts. The direct water connection with Gliwice also solved the acute problem of the lack of paved roads and railway connections. Construction was started in Zabrze. Drilling through the tunnel in the hard rock was an extremely difficult task. Two teams of miners were digging the corridor from opposite directions. Where conditions allowed, it was left in solid rock. In other cases stone and brick lining was used. They were also drilling out the shafts. Progress was much slower than expected as the work was inhibited with the difficult geological conditions. The first, a 2,5-kilometre section of the Main Key Hereditary Adit in Zabrze was opened in 1805. The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine could be drained and coal transport started. Underground ports were also built. Later on, when mining below the adit’s level of this excavation became necessary, the Main Key Hereditary Adit, gradually, started to lose its drainage significance to a large extent. What was more, the road from today’s Chorzów through Bytom to Tarnowskie Góry was completed in 1816 and through Zabrze to Gliwice in 1830. Apart from that, the Upper Silesian Iron Railway connecting the Upper Silesia with Wrocław was developed in 1846. Thus, coal wheeled and rail transport were much more efficient than underground water transport along the Main Key Hereditary Adit in the coal mining. Hence, it ceased to pay off. However, the Prussian administration continued to carry out the project to complete the Main Key Hereditary Adit. It was completed in 1863 when it was brought to the “Krug” shaft at the ‘Król” (“King”) mine in today’s Chorzów. Until the end of the 19th century, a part of mine water, pumped from deeper excavations, was discharged with it. Later on, it gradually filled with sludge and destroyed due to being unused. In 1953, its outlet was closed and a part of the Kłodnica Canal between Zabrze and Gliwice was buried. The excavation was forgotten until the idea of making it available again and using it for tourist purposes was born, in 2000. For this purpose, the Society for the Restoration and Promotion of the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit in Zabrze “Pro Futuro” was established in 2000 (Jurkiewicz, 2002; Gałązka-Salamon, 2012). Local authorities in Zabrze used to implement consistently a promotion strategy based on industrial heritage tourism. Therefore, one of its major ongoing projects, was the European Centre of Industrial Culture and Industrial Heritage Tourism. Its aim was to create an institution linking the need of preserving cultural heritage and creating the unique industrial heritage tourism attractions. Hence, by that project realization some EU funds were used for revitalization and preparing for tourists the Main Key Hereditary Adit and connecting it with the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) old workings. The goal was accomplished and a new geotourist trail was opened for public 2018, called “Underground Water Route”, connecting the Main Key Hereditary Adit with the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine by the basic drift drilled entirely in the “Pochhammer” coal seam no. 510 in the Anticlinal Beds (Fig. 3) (Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015; Gola, 2020).

The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine in Zabrze was developed in 1791 (Dzięgiel, 2007; Gola, 2020). At the beginning, the bituminous coal was extracted with the use of very simple methods. In the vicinity of the outcrop, the exploitation was of the opencast character and was carried out by means of long and deep trenches, the so-called “schurfs”. When the seams reached deeper, shallow shafts were constructed. They were managed with the use of ladders and manual windlasses. The coal extracted in this way was coked in primitive charcoal piles. Dynamic growth of the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine production enabled to develop the above model as early as in 1802. The shafts were deeper than 30 meters and connected with short galleries. Coal extraction was made by means of broad faces and shortwall drifts. Since the 1840s, the excavation of deeper coal seams began as some shafts were deepened much more, new ones were drilled and drainage systems modernized. New mining machines started to be used too. Hence, miners were able to start extracting coal from the level of 210 meters in 1868. Later on, they reached 800 meters on depth. In 1890, the first bathhouse for employees was opened there. In 1915, a new steam hoisting machine was installed in the engine room of the “Carnall” shaft (Fig. 3), which can still be watched by tourists today. After World War I the mine was divided into two independent fields: “Queen Louise West” and “Queen Louise East”, merged again in 1956, as they were in Poland. Since then, it was given the name “Zabrze”. In 1976, the mine “Zabrze” was united with the neighbouring one of “Bielszowice”, to form one of the biggest mines in Upper Silesia. Despite its great importance among Polish mines, its coal reserves were gradually being depleted, and mining finally stopped in 1998 (Dzięgiel, 2007; Żurek et al., 2010; Frużyński, 2012; Gola, 2020).

The “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Luise”) Mine also took very essential part in the dissemination and opening of underground excavations. Already in the interwar period, some part of the drifts around the “Wilhelmina” shaft (Fig. 3) were transformed into a training mine for students at the mining school. In 1985, a new, shallow set of drifts imitating the mine was built there and connected to the old excavations (Fig. 3), creating the Vocational Training and Propaganda Centre of the “Zabrze-Bielszowice” Coal Mine. It also played a demonstrative, promotional and propaganda role. In the years 1965-1979, the mine was already opened to tourists. They could go down the mine shaft and see the work on the mechanized longwall. The attraction was managed by the Intercompany Mining Branch of the Polish Tourist and Country-Lovers’ Association. In 1993, on the premises of the Centre for Vocational Training and Mining Propaganda, the Coal Mining Museum in Zabrze established its branch called “The Queen Louise Mining Open-Air Museum”. Until 1998, it took over the above-ground buildings of the former mine in the area of the “Carnall” shaft (Fig. 3) (Dzięgiel, 2007; Żurek et al., 2010; Frużyński, 2012; Gola, 2020). Some part of the underground part was available for public until 2011, when it was closed for comprehensive renovation. It was opened for tourists again in 2016, as the “Underground Family Route” (Fig. 3) (Gola, 2020).

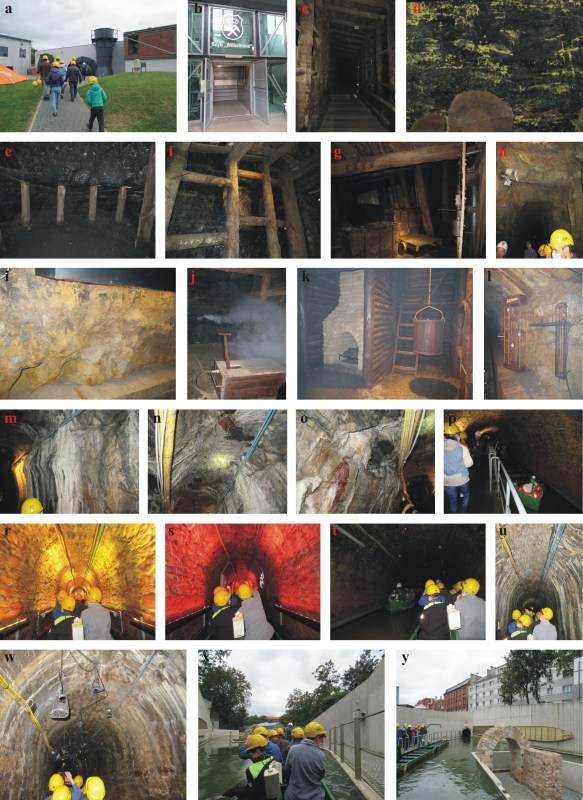

The Underground Water Route (Fig. 3) is one of the most amazing underground geotourist routes and geosites (Słomka & Kicińska-Świderska, 2004) in Poland. It starts from the “Wilhelmina” shaft brow (Fig. 3), near the ventilation station (Fig. 4a), built in 1907, whose main aim was to force the circulation of air in the underground mining works, venting it at the same time (www3). After watching it, the tourists, with a guide, descend by lift (Fig. 4b) 40 meters beneath the surface and start sightseeing the old workings of the mine. The first section of this trail the visitors pass on foot through the basic original, 19th century drift, drilled entirely in a 6-metre long coal seam no. 510, called ”Pochhammer” in the Anticlinal Beds of the Upper Silesian Sandstone series of the Upper Carboniferous (Fig. 3) (Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015). The drift connects the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Mine with the Main Key Hereditary Adit (Fig. 3) and is with reconstructed wooden lining used to protect the excavation (Fig. 4c, 4f). On the coal outcrops, the visitors can also see rosenite, mineral obtained by pyrite oxidation process (Fig. 4d) and mining face in the same coal seam with substructures of the upper coal bench using wooden racks (Fig. 4e). When they reach the former Main Key Hereditary Adit’s southern line, they can see the Reden Port, the exhibition of the reconstructed underground port, together with equipment enabling, among other things, a presentation of how coal boxes were loaded onto the boat (Fig. 3, 4g) (Gola, 2020). Then, the tourists walk along the northern adit line of the former Main Key Hereditary Adit (Fig. 3). In some sections, its working was forged in solid rock, sandstone of the Upper Upper Silesian Sandstone Series (Wilanowski et al., 2009; 2015), without additional lining but with its footwall sealed with brick troughs (Fig. 4h-i). In places, there are limestone formations on the adit lining, phenomena commonly known from caves: rillenkarrens (Fig. 4m), stalactites (Fig. 4n) and strongly weathered draperies (Fig. 4o). The visitors can also watch the exhibitions: showing an underground fire (Fig. 4j), shaft in its ladder and transport compartment, the reconstruction of the ventilation furnace used to force air to circulate underground (Fig. 4k) and mobile model of the so-called “Fahrkunst”, one of the first devices enabling the transport of people through the shaft underground and to the surface (Fig. 4l) (Gola, 2020). Last over 1,100 m of this route, filled with water, is a unique underground boat trip (Fig. 3). It starts from the port at the Brewery (Fig. 3, 4p) and runs along the former Main Key Hereditary Adit tunnel, the excavation in sandstone lining, highlighted by the lighting system (Fig. 4r-s) and is over at its mouth in the Port in the central part of Zabrze (Fig. 3, 4x-y). There is also passing loop at the Mill (Fig. 3, 4t). The tourists can also see some more of the limestone formations on the adit lining (Fig. 4u) and the exhibition of historical lamps replicas, oil and tallow ones (Fig. 4w) (Gola, 2020).

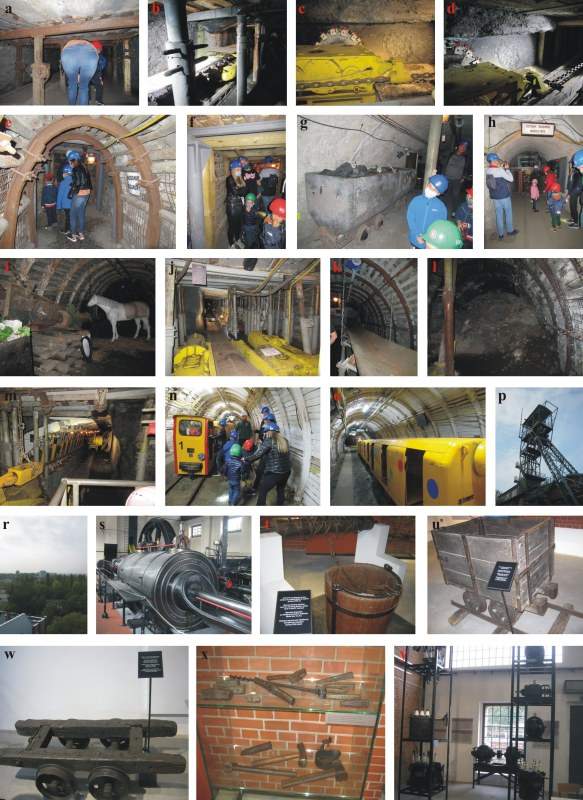

The Underground Family Route is situated 35 m beneath the surface. It also starts around the Wilhelmina shaft and runs through a mining wall on total length about 1,5 km (Fig. 3). This is an extraordinary adventure, combining the experience of authentic mine undergrounds and huge mining machines with great fun and learning, already available to the youngest tourists. In the first section of the trail, the visitors walk along very low brick lined workings, with metal props and caps (Fig. 5a). Further on, along the longwall drift lined with metal arcs (Fig. 5e), wood (Fig. 5f) and concrete (Fig. 5g-h). The tourists can see mining machines: coal plough (Fig. 5b-d, 5j) and shearer (Fig. 5m) presented in motion in a wall built with a mechanised lining. A tape conveyor, as the fragment of the system for haulage of extracted material from the longwall is exhibited there too (Fig. 5k). The tourists can also watch some old mining cars (Fig. 5g), old stable (Fig. 5i) and the bituminous coal outcrop (Fig. 5l). At the end of the trail, they can experience the travel with the historical underground railway called “Karlik” (Fig. 5n-o), which carries them along some 1,5 km. The crosscut of that railway ride is lined with steel arches and wood.

There is one more underground geotourist trail, “Tourist Route”, developed in the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex. It runs along the section of the Main Key Hereditary Adit between the “Carnall” and “Wilhelmina” shafts. But due to its renovation, it is unavailable for tourists, at present.

Around the “Carnall” shaft, some surface post-mining buildings have been adapted for tourist purposes too. Among the most recognizable are the former chain bath, a symbol of the owners’ care for the social well-being of their employees, today housing the Tourist Service Office, exhibition, conference, and catering spaces. Apart from that, there are also: the “Carnall” shaft with a hoisting tower (Fig. 5p) and two exhibitions prepared for tourists: “Amazing story. The Queen Louise Mine in 1791-1998” and “The Edison Mine”. The first one includes the “Prinz Schönaich” shaft engine room and the former mechanical workshop (Fig. 5s-x) and the second one - a 6 kV power switchboard (Fig. 5y). The most important monument of this part of the complex is the 1915 steam hoisting machine (Fig. 5s) located in the engine room of the “Carnall” shaft – the best preserved in Europe. In the former mechanical workshop, the tourists can watch the old mining equipment (Fig. 5t-x). The 31-meter high “Carnall” hoisting tower (Fig. 5p) is available for public, to enjoy viewing of Zabrze city panorama (Fig. 5r).

Apart from the underground geotourist rails and post-mining buildings, two open-air theme parks, included into the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit, have been created around the “Wilhelmina” shaft. The open-air “Park 12C” is an area of education for children and youth, as well as an area of family recreation. Right nearby is the Military Technology Park, one of the largest facilities of this type in southern Poland (Gola, 2020).

In the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit, a modern educational centre for pupils of the primary and secondary school has also been developed. They can gain a very wide knowledge by geology, thanks to those two new geotourist routes developed there (Chybiorz, 2018; www3). “Bajtel Szychta” is a unique event in the form of fun, thanks to which children can play the role of a miner and experience the hardships of working underground (www3).

Conclusions

Today, the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex in Zabrze is a post-industrial pearl of the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB). It includes the only underground geotourist routes and geosites in Europe showing how mining has been developing for the last 200 years. It is visited by hundreds of thousands of tourists every year. Authentic spaces and original mining equipment, supplemented by multimedia and reproductions of historical maps or drawings, make it easier to discover the universal history of development and transformation of other mining regions of Europe in the life of today’s adit complex. The creation of the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit complex was connected with the consistently implemented policy of the city of Zabrze, which aimed to create a tourism and cultural centre of European importance and recognised brand based on the preserved, valuable post-mining heritage. The process the adit complex revitalization has been honoured with numerous awards and distinctions. Among the most important ones is certainly the European Heritage Award/Europa Nostra Award for the conservation of adit, awarded in 2019 by the European Commission and the Europa Nostra Association in the category of conservation. In 2020, the “Królowa Luiza” (“Queen Louise”) Adit and the “Guido” mine (Dzięgiel, 2011; Gola, 2020) were recognized by the President of the Republic of Poland as a monument of history “Zabrze – a Complex of Historic Hard Coal Mines” in recognition of their exceptional values and authenticity. Thus, they were among the most valuable historic buildings in Poland and Europe which boast this distinction (Gola, 2020). Up to now, thanks to the two historical mines in Zabrze, the city plays the role of a European centre of post-industrial heritage, associated with “black gold”. Preserved underground excavations, master engineering works and mining machinery and equipment make up the richest exhibition in the country (Gola, 2020).

It is not surprising that the described objects belong to both the Silesian Industrial Monuments Route (Różycki, 2005; Nitkiewicz-Jankowska, 2006; Burzyński, 2007; Januszewski, 2009; Drobniak et al., 2020; www1; www4) and to the European Route of Industrial Heritage (ERIH). All these ones are the anchor points of the ERIH (www1).

In author’s opinion, the object described in the paper deserve to be promoted as the most interesting industrial monument and geotourist attraction in Europe and in the world. The staff of this object must be acknowledged for successful efforts to prepare the exhibitions (including natural-size figures of people and animals) and to run the excursions, in compliance with strict safety rules for underground mines. In future, when all bituminous coal resources in the Upper Silesia Coal Basin (USCB) are exhausted, there could be a chance to create some more underground geotourist trails in some other coal mines relic, still operating in Katowice, Rybnik and Jastrzębie – Zdrój (Fig. 1B). They could be very popular all over the world too.

The network of underground geotourist trails is still under development in various regions of Poland, particularly in historical mining districts of the Lower Silesia. The advantage of such objects is that these are accessible year-round and despite weather conditions, which is important for tourists, especially for those who travel with children.

The perspectives of tourist industry branch based upon the geotourist objects seem to be very optimistic.

References

Bugaj T. & Glosz M., 2012. Główna Kluczowa Sztolnia Dziedziczna. Europejski Ośrodek Kultury Technicznej i Turystyki Przemysłowej w Zabrzu. Budownictwo Górnicze i Tunelowe. Wydawnictwo Górnicze, 1: 50-62.

Burzyński T., 2007. Kierunki działań na rzecz krajowego produktu turystycznego – turystyka dziedzictwa przemysłowego. In: Dziedzictwo przemysłowe jako strategia rozwoju innowacyjnej gospodarki - IV Konferencja Naukowo-Praktyczna, Zabrze 6-7.09.2007, 27-32.

Chybiorz R., 2018. Edukacja geologiczna w sztolni Królowa Luiza. Konferencja Edukacyjna EDU-TRENDY, Zabrze 8.06.2018.

Drobniak A., Baron M., Czornik M. & Gibas P. (red.), 2020. Zabrze 2030. Strategia rozwoju miasta, UM, Zabrze, UE Katowice.

Dzięgiel M., 2007. Skansen górniczy „Królowa Luiza” w Zabrzu jako przykładowy obiekt geoturystyczny w środowisku przekształconym na terenie Górnośląskiego Zagłębia Węglowego. Geoturystyka, 4(11): 23-30.

Dzięgiel M., 2011. The “Guido” historical coal mine in Zabrze as the example of geoturism in the Upper Silesian Coal Basin. Acta Geoturistica, 1: 8-15.

Frużyński A., 2012. Zarys dziejów górnictwa węgla kamiennego w Polsce. Wydawnictwo Muzeum Górnictwa Węglowego, Zabrze.

Gabzdyl W., 1997. Geologia i kopaliny Górnego Śląska. Zeszyty Naukowe Politechniki Śląskiej 1361: 13-21.

Gałązka-Salamon E., 2012. Architektura Parku kulturowego w Zabrzu. Wydawnictwo Stowarzyszenie na Rzecz Restauracji i Propagowania Sztolni Królowa Luiza w Zabrzu „Pro Futuro”: Zabytkowa Kopalnia Węgla Kamiennego „Guido”, Zabrze.

Gola A. (red.), 2020. Sztolnia Królowa Luiza w Zabrzu – podziemna podróż w czasie. Wydawnictwo Muzeum Górnictwa Węglowego, Zabrze.

Januszewski S. (red.), 2009. Dziedzictwo postindustrialne i jego kulturotwórcza rola. Materiały konferencji Warszawa, 4–5 czerwca 2009. Fundacja Hereditas, Warszawa.

Jureczka J., Dopita M., Gałka M., Krieger W., Kwarciński J. & Martinec P., 2005. Atlas geologiczno-złożowy polskiej i czeskiej części Górnośląskiego Zagłębia Węglowego. Państwowy Instytut Geologiczny, Warszawa.

Jurkiewicz J.G., 2002. Główna Kluczowa Sztolnia Dziedziczna – najdłuższa budowla hydrotechniczna w europejskim górnictwie węglowym, Materiały Szkoły Eksploatacji Podziemnej, Wydawnictwo PAN i AGH, Kraków, 2: 773–781.

Jurkiewicz, J.G., Kolasa, J. & Wiśniewski, L., 2009. Główna Kluczowa Sztolnia Dziedziczna jako zabytek techniki zaliczany do europejskiego dziedzictwa kulturowego. WUG: Bezpieczeństwo pracy i ochrona środowiska w górnictwie, 7: 52-56.

Kotas A. & Malczyk W., 1972a. Seria paraliczna piętra namuru dolnego Górnośląskiego Zagłębia Węglowego. Prace Instytutu Geologicznego, 61.

Kotas A. & Malczyk W., 1972b. Górnośląska seria piaskowcowa piętra namuru górnego Górnośląskiego Zagłębia Węglowego. Prace Instytutu Geologicznego, 61.

Kotas A., 1995. Upper Silesian Coal Basin – lithostratygraphy and sedymentologic – paleogeographic development. In: Żakowa H. & Zdanowski A. (red.), Carboniferous of Poland. Prace Instytutu Geologicznego, 148.

Nitkiewicz-Jankowska A., 2006. Turystyka przemysłowa wizytówką Górnośląskiego Okręgu Przemysłowego. Prace Naukowe Instytutu Górnictwa Politechniki Wrocławskiej 117, Studia i Materiały, 32: 251-256.

Pawlak I. & Dziekońska I. (red.), 1974. Budowa geologiczna Polski. t. IV Tektonika. cz. 1 Niż Polski. Wydawnictwa Geologiczne Warszawa, 226-233.

Różycki P., 2005. Klasyfikacja współczesnych form turystyki. Geoturystyka, 1: 13-23.

Ruehle E. (red.), 1972. Karbon Górnośląskiego Zagłębia Węglowego. Prace Instytutu Geologicznego, 61.

Saja A., 2009. Europejski Ośrodek Kultury Technicznej i Turystyki Przemysłowej. In: Burzyński T., Staszewska-Ludwiczak A. & Pasko K. (red.), Dziedzictwo Przemysłowe jako element zrównoważonego rozwoju gospodarki - V Międzynarodowa Konferencja Naukowo Praktyczna, Zabrze, 4-5 wrzesień 2008, Katowice, 47-54.

Słomka T. & Kicińska-Świderska A., 2004. Geoturystyka – podstawowe pojęcia. Geoturystyka, 1(1): 5-7.

Stupnicka E., 2007. Geologia regionalna Polski. Wydawnictwa Geologiczne Warszawa.

Wilanowski S., Krieger W. & Żaba M., 2009. Szczegółowa Mapa Geologiczna Polski 1:50000. Arkusz Zabrze (942). Wydawnictwa Geologiczne Warszawa.

Wilanowski S., Krieger W. & Żaba M., 2015. Objaśnienia do Szczegółowej Mapy Geologicznej Polski 1:50000. Arkusz Zabrze (942). Wydawnictwa Geologiczne, 8-10.

Żurek L., Paruzel K. & Szczypkowska M., 2010. Zabrzańskie podziemia – europejską atrakcją. In: Zagożdżon P.P. & Madziarz M. (red.), Dzieje górnictwa – element europejskiego dziedzictwa kultury, 3, Wrocław: 539-551.

www1 - www.erih.net [accessed: 2011-06-08]

www2 – www.geoportal.pgi.gov.pl/css/zrozum_z/images/jkc/Rys_JKCw1.jpg [accessed: 2013.10.14]

www3 - www.sztolnialuiza.pl/index.php/pl/kopalnia-krolowa-luiza [accessed: 2019-09-19]

www4 - www.zabytkitechniki.pl/culturalheritage/1709 [accessed: 2016-12-25]